Lake Minnewaska was traditionally one of the four Sky Lakes of Shawnagunk Ridge—unique lakes noted for their extremely high clarity and almost aquamarine color. While the other Sky Lakes have maintained these features, Minnewaska is getting cloudy.

Bob Otters, who has dived at Lake Minnewaska since the early 90s as part of the Mid-Hudson Diver’s Association, has seen how the lake has changed over the years.

“Up to 2003-04, [Lake Minnewaska was] just a really great dive. Visibility was typically in the summer…maybe 20-25 feet, and sometimes, if you didn’t have any rainfall, you’d have 40 feet.”

Visibility began becoming poorer around 2006, Otters said, and is now six to eight feet during summers.

“You can get visibility of six to eight feet in probably half the lakes in the Hudson Valley…it’s nothing special anymore…there is something that has been lost there,” said Otters.

Other dramatic changes have occurred in the lake since 2006. Two species of fish have been introduced, perhaps brought in by patrons of the lake. An algal bloom in 2011 decreased visibility to less than three feet, below the level which the state deems to be safe for swimming, forcing the lake to ban swimming for a month during tourist season.

And this summer came the leeches. Though not the blood-letting variety, the state delayed opening the lake to swimmers in the beginning of the season, then temporarily closed it again in early July.

To find out the reason behind these changes, I talked to Dr. David Richardson, an assistant professor of Biology at SUNY New Paltz who has been investigating the changes; Lauren Townley, the Water Quality Program Supervisor for the New York State Office of Parks, Recreation & Historical Preservation (hereby referred to as ‘the Parks Department’ for brevity’s sake); and Jorge Gomes, the Assistant Park Supervisor for Minnewaska State Park, which includes Lake Minnewaska and two of the other Sky Lakes.

Why Sky Lakes Are So Lovely

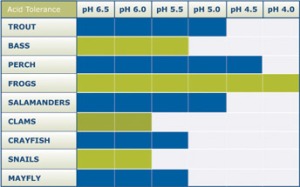

For starters, the clarity and color of the Sky Lakes are due to their high acidity. Most biota can’t survive in these conditions, leading to the Sky Lakes’ “see-through” look.

The main cause of this? Acid Rain.

“If you have real nice rainwater, you have a pH of five, five-point-five. So it’s already acidic, but the stuff that’s been impacted by fossil fuel production—especially coal-fired power plants—[it’s] lowering the pH of rain to 4, under 4,” said Dr. Richardson.

This acid rain forms over industrial cities in Michigan, Ohio and Western Pennsylvania, then is carried over the Hudson Valley and Upstate New York by prevailing weather patterns

Lakes in the Adirondacks have been most adversely impacted by acid rain. There, highly-acidic lakes carry the less-attractive moniker of “Dead Lakes.”

The geology of the Shawnagunk Ridge has helped accentuate the low pH of incoming rain.

Dr. Richardson explained that the Shawnagunk Ridge is geologically distinct from the Appalachian Mountains, which form the majority of mountains on the East Coast, including the nearby Catskills. While the Appalachians were formed roughly 480 million years ago, the Shawnagunks were formed during the last ice age, which lasted from about 110,000 years to 12,000 years ago.

During this period, glaciers moved down from Canada, gouging out softer rock along the way. However, the vein of quartz conglomerate that would become the Shawnagunk Ridge was too hard to gouge out, so it remained mostly intact. When the glaciers receded, the areas around the vein were gouged to a lower elevation, leaving the quartz conglomerate as a ridge.

This quartz conglomerate is only thinly covered with soil.

“When you have really thin soil, or you have bare rock, it almost acts like a bathtub…the lakes are just collecting rainwater, so they reflect what the chemistry is in the rain, and that means really low pH,” said Richardson.

Non-Sky Lakes in the region sit on shale or other rock more susceptible to erosion, allowing more soil to form. The soil, as well as the shale itself, acts as a buffer for acid rain, making these lakes more neutral.

In 2008, Jorge Gomes began anecdotally hearing about a small fish species in the lake. The summer of 2009, the presence of the Golden Shiner, a “bait fish” a few inches long, was established by the Parks Department.

It was the first time Gomes had ever seen a fish in Minnewaska.

Though new to the lake, the Golden Shiner is technically not an invasive species—it can be found all around the Northeast. However, the Shiners had no predators in the lake, causing their population to explode and cause what Lauren Townley referred to as a “trophic cascade.”

“When people had considered it a dead lake, that wasn’t really accurate,” she explained. “There was phytoplankton surviving, and there was also zooplankton…when the fish were introduced, they ate the zooplankton, so the zooplankton was not in that much abundance to feed on the phytoplankton, so the phytoplankton population exploded.”

This caused the algal bloom of 2011, forcing the Park Department to ban swimming in the lake.

“The lake turned this PCB green color,” said Townley. “We were very concerned…park managers were very concerned…people that have been coming to the lake for decades expect it to be this clear color…something obviously very big was happening with the lake.”

Townley studied data from the Parks Department and the neighboring Mohonk Preserve, and found that pH levels had been slowly rising for the last couple decades.

“But, for some reason, there was a kind of a tipping point where [Minnewaska] was able to sustain fish and other types of biota,” said Townley.

The new life came at the expense of the old. Richardson reported that the changes in the lake caused the die-off of Sphagnum Moss (also known as Peat Moss), which covered up to 60% of the lake’s bottom. The moss was able to absorb sunlight due to the high clarity of the water, but an increase in the biota blocked this light.

Other species thrived in the lake when it was more acidic, including two rare salamander species and various microorganisms. However, said Richardson, “most of them can survive pretty well in less acidic environments.”

Causes of the Change

“The major impact that we think has had an effect on pH is a reduction of acid rain because of legislation,” said Townley, “The Clean Air Act has limited the amount of acid rain across the country, so we’ve seen a recovery in the lakes.”

This can be seen in lakes across the Northeast. However, the recovery of the other Sky Lakes in the Shawnagunks has been very gradual. Lake Awosting, situated less than three miles Southwest of Lake Minnewaska, still has a pH below 5, whereas Minnewaska’s pH is nearly 7, according to Townley.

There are several theories as to why Minnewaska is rife with biota while the other Sky Lakes still are too acidic to support life.

One of the theories, explained Richardson, goes back to the Shawnagunk’s geology. Though the Ridge is comprised of quartz conglomerate, the hard rock sits atop a layer of shale. The quartz conglomerate thins towards the Ridge’s Northern end, the shale underneath reaching closer and closer to the Ridge’s surface. The conglomerate is thin enough around Mohonk Lake—another body of water on the Shawnagunk Ridge—for the lake’s bottom to dip through the conglomerate and rest on the shale. The shale’s acid-buffering qualities have never allowed Mohonk Lake’s pH to dip low enough for it to have the attributes of a Sky Lake, and it has always had fish.

Dr. Richardson theorizes that a small portion of Lake Minnewaska might similarly dip into the shale layer, causing the water to be slowly leeched of its acidity.

Dr. Richardson theorizes that a small portion of Lake Minnewaska might similarly dip into the shale layer, causing the water to be slowly leeched of its acidity.

Divers, including Otters, have searched for such an area, but have had no luck so far.

A shale mixture is used on Minnewaska’s carriage roads. The run-off from the roads might also be raising the lake’s pH.

Another theory has to do with the hotels that used to surround Lake Minnewaska.

“There were a couple different hotels, and they had a water pump that was operated by coal that pumped the water up to hotels,” elucidated Richardson. “They would just take the ash from the coal and chuck it into the lake.”

The ash from burnt coal, explained Richardson, includes phosphorous and other chemicals which can buffer acidic lake water.

Though the reasons behind Lake Minnewaska’s more rapid return to a near-neutral pH are still under investigation, the history of the region’s lakes—specifically their high acidity in modern times—can be attributed to human industrial development.

Now that the impacts are being softened, Lake Minnewaska is returning to its former state. Life is abounding.

The irony is that this might not be what we want.

The Leeches

Though it is unknown where the leeches currently populating Lake Minnewaska come from, the species does not take well to high acidity, and wouldn’t be able to survive in Minnewaska before the changes of the last few years.

Though completely harmless to humans, Gomes said “there’s still a fear factor or level of uncomfortableness that people have with leeches.”

The leeches have “definitely impacted swimming attendance,” said Gomes. Overall attendance is down slightly from last year.

Gomes said lifeguards were on hand to explain to swimmers that the leeches were not dangerous, and signs had been put up showing how small the leeches were.

“But there’s definitely less people in the water, that’s for sure,” said Gomes.

However, the changes in Lake Minnewaska have yet to dramatically impact attendance. This is good, since Minnewaska State Park attracts more than 210,000 visitors a year, according to a report by the Parks department, helping support New Paltz and other surrounding communities.

I asked Dr. Richardson about the potential irony of Lake Minnewaska’s natural state being a deficit to people who want to experience nature.

“Humans like to think about nature in terms of what we’ve seen in our lifetimes. We like to harken back to the time when we were kids, and the conditions when we were kids, but if you look at the history of the lake over a more ecological timeframe, Minnewaska might have been acidic, and then not acidic and then acidic.”

When people ask him as an ecologist whether the changes are good or not, Richardson said he likes to respond thusly:

“It’s a change and it’s been a very rapid change. It‘s not good or bad. It’s different then what we’ve seen in the past.”