Temperatures are expected to rise in the Hudson Valley and Catskills more drastically than most of the U.S. due to climate change, with the region seeing temperatures four-to-five degrees higher by 2050 when compared to the late 20th century.

These predictions come from the Fourth National Climate Assessment, a voluminous report produced by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and 12 other federal agencies every four years to inform stakeholders about expected changes from Global Warming.

The report specifies many changes the Northeast should see from the temperature increases, including heavier rain, increases in infectious disease, die-offs of plants and animals, changes in agriculture, and mass migration.

I talked to experts in these fields to see how these effects could — and in many cases, already are — impacting the Hudson Valley and Catskills.

A Rising River and Mass Migration

The Atlantic Ocean off the coast of the Northeast is expected to rise two-4.5 feet by 2100, according to the assessment, far greater than in most parts of the world.

A variety of factors contribute to this regional spike, including changes in sea currents leading to higher ocean temperatures than most of the world, causing thermal expansion, and North America sinking due to glacial melt, according to the assessment.

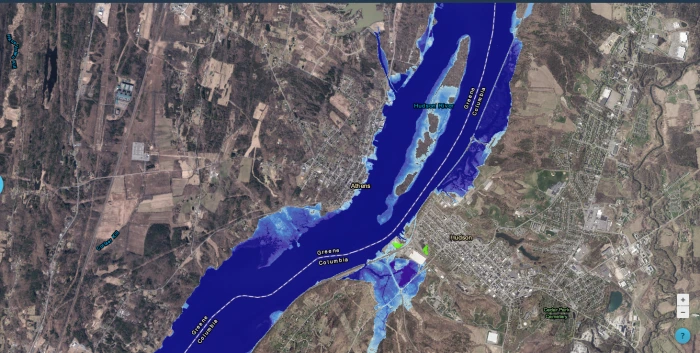

The Hudson River is at sea level from New York City north to the Federal Dam in Troy, so the river will rise at the same rate as the Atlantic.

Hudson River communities will not flood to the same degree as many parts of the U.S. from the rise, thanks to the Hudson River’s steep banks, according to the NOAA’s Sea Level Rise Viewer.

However, this is far different than saying there will not be flooding. The Beacon Waterfront Park and Kingston Point Park will be cut off from the mainland. Much of Athens’ waterfront, in Greene County, will be underwater. The South Bay, just outside of Hudson, will greatly expand, lapping at the doorsteps of industrial buildings. Sections of the rail line running along the Hudson’s east bank, which carries both freight trains and Amtrak passengers, will be submerged, according to the viewer.

New York City and its environs will fare much worse under a 4.5-foot sea level rise, with neighborhoods in Queens, the south shore of Long Island, and Bergan County, New Jersey inundated with water, potentially displacing hundreds of thousands of people.

The coasts of Massachusetts, New Jersey and New York “are anticipated to see large outflows of migrants” due to the rising waters, according to the analysis, “a pattern that would stress regional locations further inland.”

These potential impacts are based on the 4.5-foot rise, the higher end of the assessment’s moderate predictions. The northeastern seaboard — and therefore the Hudson River — could see up to an 11-foot water rise by 2100, according to the assessment’s worst-case scenario, drastically re-shaping the geography of New York City and the Hudson Valley.

Lyme and Other Diseases

“Vector-borne diseases” — those transmitted by ticks, mosquitoes and fleas — are expected to increase in the Northeast due to the broadening ranges of their hosts, according to the assessment.

The assessment specifically mentions Lyme disease, the confounding tick-borne illness that has infected tens of thousands in the Hudson Valley during the last couple decades. Increasing temperatures will extend the period of elevated risk for transmission up to three weeks earlier in the spring by 2080, according to the assessment.

Mary Beth Pfeiffer, author of “Lyme: The First Epidemic of Climate Change,” and a former Poughkeepsie Journal reporter, draws a direct link between climate change and Lyme.

“There is a great deal of scientific evidence that shows this correlation between a warming world and the spread of, and proliferation of, ticks,” she said.

Ticks capable of carrying the disease are spreading northward in the Northern Hemisphere and southward in the Southern Hemisphere, with the range of these ticks in Norway increasing more than 400 miles north in the last 40 years, Pfeiffer said.

Canada is the “new frontier” for Lyme, Pfeiffer said, and is “very much where we in the Northeast were a quarter-century ago.”

Ticks infected with the disease from biting white-footed mice pass it to humans during their nymph stage. The malady can cause neurological and cardiac problems and is often misdiagnosed as rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, Alzheimer’s disease, or even psychiatric disorders, Pfeiffer said.

In 2017, counties in the Hudson Valley and Catskills reported between 32-58 percent of their deer ticks were infected with Lyme, a huge increase from 2008, when between 6-40 percent of ticks were infected, according to the New York State Department of Health.

Deer ticks can also transmit Anaplasmosis and Babesiosis. Ten percent of ticks in Columbia County in 2017 tested positive for Anaplasmosis and almost three percent were infected with Babesiosis, according to the state Department of Health.

Lyme is on the increase not only because of increasing temperatures, but the “perfect storm” of human alterations to the environment, Pfeiffer said, including forests diced by development into sizes perfect for the white-footed mouse, and the extinction of predators that normally keep mice and white-tailed deer populations under control.

Zika, a tropical disease that can cause major birth defects, is expected to increase in the Northeast due to the increased range of its host, the tiger mosquito, according to the assessment.

Zika, originally found only in Africa, exploded in Brazil in 2015, going onto infect hundreds of thousands of people in Latin America that year, according to the World Health Organization.

Shannon LaDeau, a disease ecologist with the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, said the tiger mosquito has been spreading since it was unintentionally introduced in Maryland and Florida in the 1980s.

Though the reason is unknown, the strain of tiger mosquitoes currently in the U.S. have a northern limit, LaDeau said, and are not generally found north of New York City.

However, “as the winter season becomes shorter and you get more time during the summer for the population to build up, it will become more problematic, and it will become more likely to move further north,” she said.

Though there have been hundreds of cases of Zika in New York City, those infected picked up the disease abroad. Zika has not been established in tiger mosquitoes in the Northeast, mostly because those who travel to the Caribbean and South America do so in the winter. When these people get back, it’s not mosquito season, and therefore the disease does not infect local tiger mosquito populations, LaDeau said.

“We have this kind of mismatch that’s been protecting us, but as the mosquito season gets longer, those kind of mismatches aren’t as protective,” she said.

It is “certainly the expectation” the disease will become established in the Northeast, as well as other tiger mosquito-borne diseases, she added.

Mary Beth Pfeiffer said ecotourism in the Hudson Valley has not yet been widely impacted by fears of Lyme, because “a lot of people don’t know the risks when they go to a particular place.”

“The more important thing…is to educate people as to how they prevent themselves from being bitten when they commune with the natural world, because we can’t stop doing that,” she said, “We shouldn’t stop doing that — it’s really good for us.”

Flooding & Agriculture

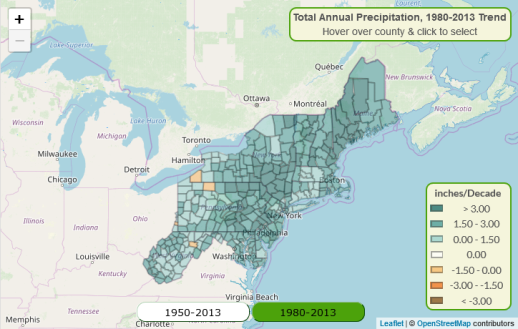

The Northeast is expected to get wetter due to Climate Change, according to the assessment, with the region getting an additional inch of rain every month from December through April by the end of the century.

The effects are already being seen. Yearly precipitation in most of the Hudson Valley increased three inches from 1980-2013, with Greene County picking up almost six inches more, according to Cornell University’s Climate Smart Farming initiative.

The rain will more frequently come in bursts, according to the assessment, leading to more inland flooding.

The more frequent and heavier rains could negate the only positive impact the assessment lists for the Northeast — a longer growing season.

The season — defined as the time from the last frost of spring to the first frost of fall — could increase by almost two months by the end of the century under the assessment’s more drastic prediction. This would arguably be a boon for Hudson Valley farmers.

However, “If the trend in the frequency of heavy rainfall prior to the last frost continues, overly wet fields could potentially prevent Northeast farmers from taking full advantage of an earlier spring,” the assessment reads.

Laura McDermott, a small fruit and vegetable specialist with the Cornell Cooperative Extension, said she is weary of making specific predictions with regards to Climate Change, but was able to theorize based on data and observations by her and others at Cornell University.

“The rain is really a problem,” she said. “It’s especially a problem for our annual crop growers and vegetable growers, because they have tilled ground…(that) is much more vulnerable to run-off and flooding.”

The assessment specifically mentions tree fruit, and McDermott said apple crops were already being impacted in the Hudson Valley.

Apple trees rely on a period of winter dormancy brought by cold temperatures followed by a warm-up in spring uninterrupted by late frosts.

The next year’s crops can be damaged if a warmer winter doesn’t allow a dormant period, because the trees are less hardy and can bloom too early, McDermott said, then be damaged by a late frost. Early warm temperatures exacerbate the problem.

Blueberries, peaches, pears, and, to a lesser extent, grapes, all face a similar predicament, she added.

In 2012, an early bloom followed by a late frost destroyed fifty percent of New York’s apple crop, McDermott said.

Many potential problems for Hudson Valley agriculture come down to unpredictability, McDermott said.

“People are reluctant to invest,” she said. “It’s very expensive to put an acre of tree fruit in, so if you don’t have confidence you’re actually going to get them through the winter, even if you knew that you could grow them through the [summer], would you do it?”

Heavier rain will result in increased erosion and agricultural run-off, which could affect drinking water, according to the assessment, a real problem for the Catskills, where New York City gets most its drinking water.

Oh Yes, and Nature

The assessment generally focuses on how humanity will be affected by climate change, especially their collective pocketbook.

However, the assessment also paints a grim picture of how the natural world will be impacted in the Northeast.

Warmer temperatures are expected to lead to die-offs of conifers at high elevations, such as those found in the Catskills. Freshwater life such as salamanders, invertebrates, mussels, trout, and other cold-water fish are expected to be drastically diminished. The habitats of dragonflies and damselflies, “species that are a good indicator of ecosystem health along rivers” are expected to decline 45-99 percent by 2080 in the Northeast, according to the assessment.

The assessment mentions an issue of special concern to the Catskills — the continued spread of the Hemlock Wooly Adelgid (HWA), an invasive species that destroys the Hemlock tree, a keystone in the region’s environment.

Katherine Nadeau, deputy director at Catskill Mountainkeeper, said it would be “a humongous, humongous problem” if the existing HWA population in the Catskills took off.

“The warmer winters make it easier for the bug to reproduce,” she said. “Then there’s a huge domino effect of environmental changes. If we start losing this foundation species…then that’s going to impact tons of other wildlife.”

One-in-three trees in New York are Hemlocks, Nadeau said, and those in the Catskills often cool streams and rills with their shade, and a die-off would increase temperatures up and down the waterways, affecting everything that lives in them, including the much sought-after trout.

Nadeau has seen the HWA spread northward with increasing temperatures, the pest appearing in the Finger Lakes this year.

An important part of the climate assessment was the authors’ assertion “that the decisions we make today will have a big impact on future options and how extreme or not climate change impacts could be,” Nadeau said. “…we can do the right thing now to prevent some of the worst of this.”

Nadeau mentioned the “New York State Climate and Community Protection Act” a state bill seeking to limit greenhouse gases and transition the state to renewable energy.

The bill passed the Assembly earlier this year, then stalled in the Senate, but Nadeau said with a legitimate democratic majority in the assembly after November’s elections, she feels the bill will pass.

Correction: This article has been updated to reflect the county Lyme counts are from the NYS Department of Health, not the individual counties’ health departments.

Pingback: ‘A Terrible Thing’ - New York Slashes Funds for Lyme Research