Researchers from France to Dutchess County are searching for new ways to combat Lyme, a potentially debilitating disease ticks pass to more than 75,000 New Yorkers each year.

Researchers from France to Dutchess County are searching for new ways to combat Lyme, a potentially debilitating disease ticks pass to more than 75,000 New Yorkers each year.

The Hudson Valley is the epicenter of Lyme in New York. Nine out of the 10 counties with the highest rates of Lyme in the state are in the Hudson Valley and Capital District, according to the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH). Greene County has the highest rate in the state.

Lyme isn’t the only tick-borne disease (TBD) affecting the area. Columbia County had the highest rates of three other severe TBDs in 2017, according to NYSDOH. The Powassan virus, another TBD, killed an Ulster County man last month.

As TBDs spread through the U.S. and around the globe, scientists are developing novel new methods to combat them. Here are four of them.

A Lyme Vaccine

Valneva, a multi-national biotech company, has created a Lyme vaccine currently undergoing testing by the FDA.

The vaccine seeks to stop the Lyme bacteria – Borrelia – from migrating from the mid-gut of ticks to its human host after a bite.

Ticks acquire Lyme disease when they feed on a mouse or other Lyme-infected mammal during the early stages of their life, and carry it in their mid-gut as they develop. When a tick feeds on a human, Borrelia migrates from the mid-gut into the human’s bloodstream, infecting them.

VLA15, the working name for the vaccine, consists of an outer-surface protein found on Borrelia that, when injected into humans, creates an immune response as the body produces antibodies. When a vaccinated person is bitten, the antibodies enter the tick before the Borrelia migrates up from the tick’s mid-gut, keeping the disease in the tick, according to Valneva.

Valneva started the second of three phases of FDA trials this July, aiming to find the correct dosage of the medicine, which is given in three separate shots.

VLA15 is the only Lyme vaccine currently undergoing clinical trials, which were given a Fast Track designation by the FDA, according to Valneva.

This is not the first Lyme vaccine.

In 1998, the pharmaceutical company SmithKlineBeecham (now GlaxoSmithKline) released LYMErix, but four years later, the company voluntarily withdrew the vaccine from the market.

LYMErix received a “guarded endorsement” from an FDA advisory group in 1998, with the group’s chair saying it was “rare that a vaccine is voted on with such ambivalence,” according to the endorsement.

The group expressed concern the vaccine would lead to autoimmune disorders, especially arthritis. In 1999, a class-action lawsuit was filed seeking damages for patients who received the vaccine and claimed they developed arthritis because of it.

However, the lawsuit was settled without any money going to the litigants, and a study by the FDA following up on LYMErix found vaccinated patients were no more likely to develop arthritis than anyone else, according to The Lyme Vaccine: A cautionary tale, a paper released in the medical journal Epidemiology and Infection.

However, Jill Auerbach, a long-time TBD advocate who chairs the Hudson Valley Lyme Disease Association, said there was “no doubt” Lymerix caused autoimmune disorders.

VLA15 works similarly to LYMErix, but it is a different vaccine promising to protect against a wider range of Borrelia serotypes, and has the benefit of 20 more years of understanding behind it.

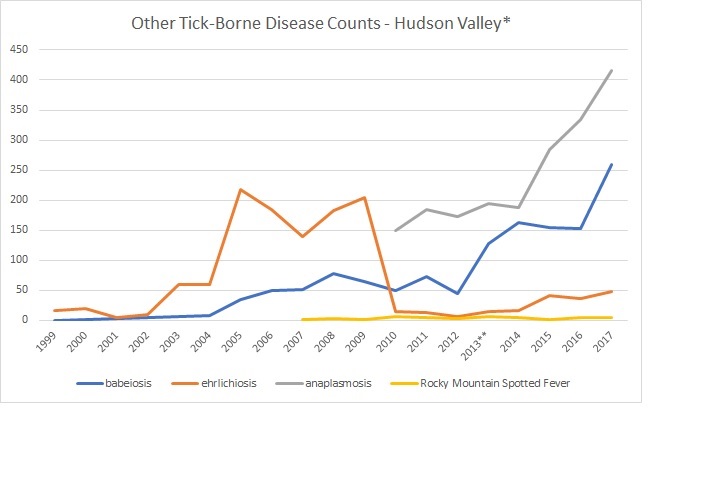

Number of non-Lyme TBD cases reported in the Mid- and Upper Hudson Valley. All numbers are from NYSDOH.

But Lyme advocates said any vaccine given to humans to prevent Lyme would not be getting at the problem’s root.

“A Lyme vaccine will do absolutely nothing to fix the problem,” Auerbach said, opining Lyme should instead be addressed before an infected tick bites a human.

A Lyme vaccine would also only address one TBD, Auerbach added, and those who receive it might be less cautious around ticks, which still can carry other TBDs.

Mary Beth Pfeiffer, the author of “Lyme: The first epidemic of climate change,” also pointed to the other diseases ticks can carry.

“We need more than a vaccine that stops Lyme disease alone, although a safe, effective vaccine would be welcome in the interim,” according to Pfeiffer.

She pointed to babesiosis, the third-most common TBD in New York, as a disease a Lyme vaccine would not address.

“We need a vaccine that works against ticks themselves, forcing them to quickly detach or even killing them,” according to Pfeiffer, who added more research also needed to be done on stopping ticks in the environment.

Vaccinating Mice

US BIOLOGIC wants to stop Lyme disease before it reaches humans.

The Memphis-based biotechnology company has developed a Lyme vaccine promising to clear Borrelia from the ticks themselves.

The vaccine is not given to the ticks directly, but to mice, the “reservoirs” of Lyme disease, in vaccine-laced food pellets, according to US BIOLOGIC.

If a mouse is cleared of Borrelia, the disease is stopped in its tracks before it is passed onto ticks, and then humans.

Furthermore, if a Lyme-infected tick bites a vaccinated mouse, the tick will be cleared of Borrelia, neutralizing its ability to infect humans with the bacteria, according to US BIOLOGIC.

US BIOLOGIC President and CEO Mason Kauffman said vaccinating mice, instead of humans, “kind of steers (us) away from any type of controversy.”

When vaccinating mice, there is no debate between pro- and anti-vaccine camps and no controversy over how the vaccine could affect diagnostic tests, Kauffman said, who described the vaccine pellets as preventative.

The vaccine was developed by Maria Gomes-Solecki, who worked off a similar formulation appearing in the LYMErix and VLA15 vaccines.

Gomes-Solecki tested the method in Dutchess County with the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies through a grant by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, according to US BIOLOGIC.

Gomes-Solecki tested the method in Dutchess County with the Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies through a grant by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, according to US BIOLOGIC.

The five-year study resulted in a 76 percent reduction in Lyme-infected ticks, Mason said, but the number would probably be higher if the study went on for longer.

“What you would find is if you [distributed the vaccine] for six years, it’d probably be 80 percent, if you did seven years, it’d probably be 85 percent, because there’s a compounding effect,” he said.

Though Mason specifically states the vaccine pellets would not eradicate Lyme, if they are distributed consistently in an area, herd immunity would develop – even unvaccinated mice would be less likely to carry Lyme, since there would be less infected mice and ticks to give it to them in the first place, he said.

The vaccine is currently moving through the regulatory process, and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) must approve the pellets for them to be sold.

If the product is approved, the company has ambitions to distribute the pellets through a variety of channels. The company hopes to bring their product to public lands through federal and state agencies such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and the NYSDOH, to homes through pest-control companies, and eventually into the hands of consumers through retail stores.

Killing the Vector

Small rodents – particularly white-footed mice – are Lyme disease’s reservoir, holding the disease. Ticks are the disease’s vector, allowing the spread of Lyme to humans.

Though Lyme is the number-one disease in the Hudson Valley that uses ticks as a vector, there are others. More than 150 people in the Mid- and Northern Hudson Valley were infected with Babesiosis in 2016, according to the NYDOH, a parasitic infection that can cause flu-like symptoms and anemia. More than 330 were infected with anaplasmosis that year, according to the NYSDOH, which, if not treated, can lead to organ failure and death.

The Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies in Dutchess County wants to fight Lyme and other TBDs by limiting tick populations.

“The Tick Project,” is testing out two tick-killing methods in two-dozen Dutchess County neighborhoods: one involves spraying a tick-killing fungus, and the second involves luring mice and other tick-carrying mammals into a “bait box,” where they would brush against a wick containing fipronil, the tick-killing agent in Frontline.

Cary Institute Disease Ecologist Rick Ostfeld explained how volunteers’ property was sprayed twice a year with the fungus, metarhizium Brunneum, while 4-5 bait boxes were set up in each yard.

Both metarhizium Brunneum and fipronil are commercially available, Ostfeld said.

“We didn’t want some experimental, unreleased, unavailable product to be part of our experimental trials, because, if it worked, it would be very frustrating if one could not adopt the system in the real world,” he said.

It’s already known that metarhizium Brunneum and fipronil kill ticks; the experiment is focused on whether these methods significantly cut down on the number of people being infected by TBDs.

Prior research by other groups suggests the experiment could go either way, Ostfeld said.

Ostfeld is concerned about people applying environmentally damaging chemicals to their properties to get rid of ticks, chemicals that may have zero effect on whether they will contract a TBD, he said.

If the chemicals have no effect, “I guess the best-case scenario is you’ve just spent money that you didn’t need to spend, and you haven’t really influenced your family’s health one way or another,” he said. “The worst-case scenario is you spend all this money spraying your property, and if it’s with a chemical, then you’re killing non-target organisms, you’re killing bees and butterflies, spiders, things you don’t necessarily want to kill.”

Ineffective products can also give users a false sense of security in their yards, leading to less diligence and more infections, he added.

Metarhizium Brunneum is not environmentally damaging, Ostefeld said, killing ticks “and almost nothing else.” The fungus is native to New York.

Distributing the fungal spray and the bait boxes is labor- and time-intensive, and Ostfeld said the idea was not to distribute the methods over the entire state or country, but instead to focus on “the most high-risk areas.”

Deleting Tick Genes

Monika Gulia-Nuss, a vector biologist at the University of Nevada, Reno, is experimenting on the genetics of ticks in hope of finding a way around TBDs.

She uses CRISPR technology, often referred to as “gene editing,” which involves injecting a cell with an enzyme that acts like a pair of molecular scissors, allowing scientists to remove genes.

Once Gulia-Nuss developed a way to inject tick eggs with the enzyme, she was able to begin deleting different genes to see what effect they had on the resulting hatched tick.

“Now we are moving in to find a protocol to develop this tool in a way we can understand functions of different genes, different proteins, and [this] will possibly allow us to figure out what genes are needed for pathogen development inside the tick, and which genes…eventually [allow] the tick to feed on vertebrates,” she said.

Gulia-Nuss is primarily looking at how ticks’ reproductive and feeding cycles could be disrupted, she said.

This research could eventually be used in the development of a new vaccine, or a way to kill or neuter ticks in nature, Gulia-Nuss said, adding the latter was important because ticks would eventually become immune to traditional pesticides.

Though results are 5-10 years down the road, Gulia-Nuss said, the project hopes to find a way to not only prevent Lyme, but all TBDs.

“We can control Lyme disease, or we can control the tick that can spread Lyme disease, and if we can control the tick, we can control multiple different diseases,” she said.

Afterword: The Sadness of Lyme

I’ve been reading a lot of about Lyme lately as part of my effort to write more on the subject, since I believe it’s one of the two big stories in the Hudson Valley’s narrative.

[ppp_patron_only level=”9″ silent=”no”]

The two thickest items I’ve read so far, the 2018 Report to Congress on TBDs and Mary Beth Pfeiffer’s excellent book “Lyme: The first epidemic of climate change,” contain stories of those afflicted with long-term Lyme and other TBDs.

They are incredibly sad.

These diseases destroy lives…I read them, and imagine my good health being replaced by constant pain, fatigue, depression and senility. My adventures in nature, whether they be hiking, kayaking or bird watching, would be no more. I would not have the strength.

I’ve never had Lyme (knock on wood), which is almost odd, since I’m in the woods so often (KNOCK, KNOCK). I wear long pants and bugspray, but I’d be lying if I said I consistently did tick checks.

Lyme is something to fear in the Hudson Valley, and these stories make me realize it.

I’ve found myself being a bit nervous in nature, of the plague.

-Maybe you should play it safe, Roger. Cut down on the adventures in nature, the hiking, kayaking or bird watching. You don’t want to end up disabled.

-I see your intended irony there – you wouldn’t be in nature either way. But you’re not active 24/7 or anything, and if you had Lyme, EVERYTHING, whether indoor or outdoor, would suck.

-This is what I fear, though: nature in the Hudson Valley becoming a no-go zone. I’m not going to contribute to that.

-Well, good luck with that. Moron.

KNOCK. KNOCK. KNOCKKNOCKKNOCKKNOCKKNOCKKNOCK….

[/ppp_patron_only]

Interesting article. I’m glad people are working on this from multiple angles.

We have a place up on the mountaintop, in East Jewett which is still Greene Co. We haven’t seen a deer tick in years, but lots of dog ticks this year.

We went to the east end of Long Island in late June and saw a few deer ticks on the kids. (More in one day than five years in the Catskills.) I had a fever and a rash in early August which was (mis)diagnosed as cellulitous. Fast forward to Labor Day weekend and I was in the ER with a fever, a rash three to four times the size as before, severe joint pain in my knee, jaw, and top half of my spine and neck.

Two doses of doxycycline as I was already on the mend. One more week to go.

I wonder how different the tick populations are in the Hudson Valley versus up in the mountains. It seems like the county borders don’t necessarily accurately reflect the tick distribution.

Huh – interesting. I’d like to talk. My email is hannigan.gilson@gmail.com. Could you shoot me an email with your contact info (AKA a blank email), and I’ll get back to you?